Prairie Dogs

/Okay, so I'm on an animal kick lately. Colorado does that to me. Among other animals, we saw coyote, deer and marmots on our trip there a couple of weeks ago. And, of course, we saw prairie dogs. When Lewis and Clark first explored the area in 1806, they described them as barking squirrels. The French trappers, however, had already named them chien de prairie and that name stuck. If you're from Colorado or that part of the country, prairie dogs aren't a big deal. They sometimes call them sod poodles or chiselers. If you're not from the area, however, they're fascinating, industrious little critters. Rodents … but cute … in a hamster, bunny sort of way.

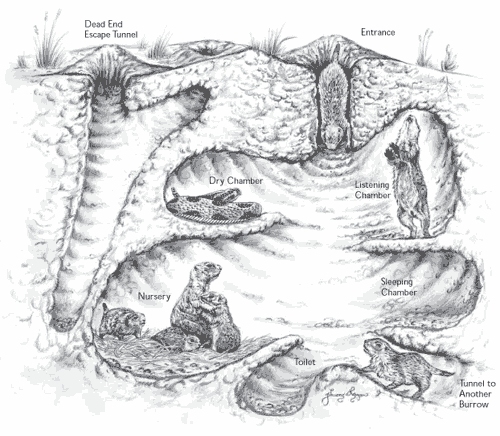

It's hard to miss them. The ones we saw were black-tailed … one of the five known species. They set up their towns with elaborate burrow systems in almost any free, open space that sports a little grassy vegetation. Though humans constantly encroach on their turf, prairie dogs are very resilient and forgiving. They just move on and find new digs … literally. Dog towns are found even in urban areas … mostly vacant lots.

They kind of remind us of the meerkats we saw in Africa. They stand guard at the entrance to their burrows and then bark and whistle to alert the rest of family and town when a predator approaches or onlookers get a little too close. They all pop their heads out of their burrows when there's an unexpected noise or event.

In actuality, the whistles and barks have been found to be a rather sophisticated system of communication describing specific predators... not only what they are are, but how big, how close and the perceived level of threat.

We used to use the term “prairie dogging” at our company when we all worked in cubicles. Whenever there was a noise or distraction, everyone would poke up their heads to see what was going on.

We've seen the world's biggest prairie dog in Cactus Flats, South Dakota.

And a coterie of white prairie dogs in South Dakota, too.

If you're a rancher, these guys are considered pests. They make so many burrow holes that your cattle and horses trip on them or get their feet stuck. If you're a farmer, they can damage your crops. They don't usually eat the crops, they just clear all the vegetation around their burrows which tends to include your lettuce. They're varmints and considered not only expendable, but provide target shooting entertainment … like rats at the dump. They schedule prairie dog shoots as local events in some areas. There are actually recipes on line for prairie dog. I guarantee they won't be included in the Nine of Cups Cookbook. There's even a prairie dog video game you can download which seems much more fun to me than killing a live one.

Unfortunately, these guys are also susceptible to the bubonic plague aka the Black Death (from fleas) and tularemia aka rabbit fever (from ticks and deer flies), bacterial diseases which can spread to humans if they handle diseased animals or get bitten. My reading indicates that the chances of getting either disease from a prairie dog are about as likely as getting struck by lightning. According to the Mayo Clinic, the risk of contracting the bubonic plague worldwide is 1 in 3 million. The CDC indicates an average of only seven human plague cases are reported in the US each year.

Prairie dog numbers have declined significantly since the days of Lewis & Clark. What a surprise, huh? Ecologists consider them to be a keystone species. That is, they're the primary diet for ferrets, fox and eagles among others. They make tasty snacks for some snakes as well. Additionally, their burrows are borrowed by some birds like plovers and burrowing owls for nesting. An additional 117 wildlife species likely benefit from prairie dog colonies to meet their biological needs.

There's even a Prairie Dog Coalition that, in conjunction with the American Humane Society, has stepped up to provide some protection for these guys. I'm more inclined to writing blogs and taking photos than standing on a soapbox, but you gotta wonder about us humans sometimes ...