What's the Sperrgebiet...

/and why can't we go there?

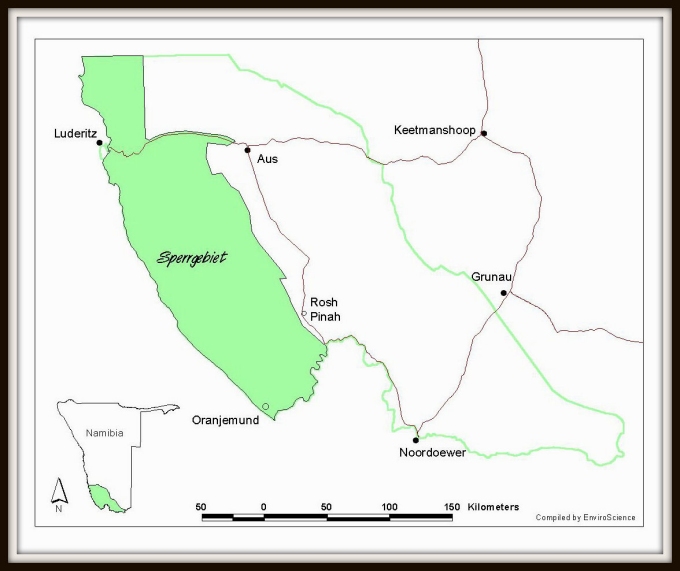

Sperrgebiet (pronounced spur-geh-beet) translates from the German to “Forbidden Area”. It's also known as Diamond Area 1 and it's the exclusive diamond mining area of southwestern Namibia. It extends along the Namibian coast from the South African border at Oranjemund for about 200 miles (320km) north ... about 45 miles north of Luderitz. It covers about 10,400mi² (26,000km²) in land area and the public has not been allowed within its boundaries without a special permit since 1908 when it was created. It extends inland about 100km (60 miles) and out into the Atlantic Ocean about 5-6 miles. We noted “Restricted Area – Marine Mining Vessels – Entry Prohibited – Minefields” warnings on our charts all the way up the coast to Luderitz. There are no ports or anchorages along this stretch of coast at which we were allowed to stop.

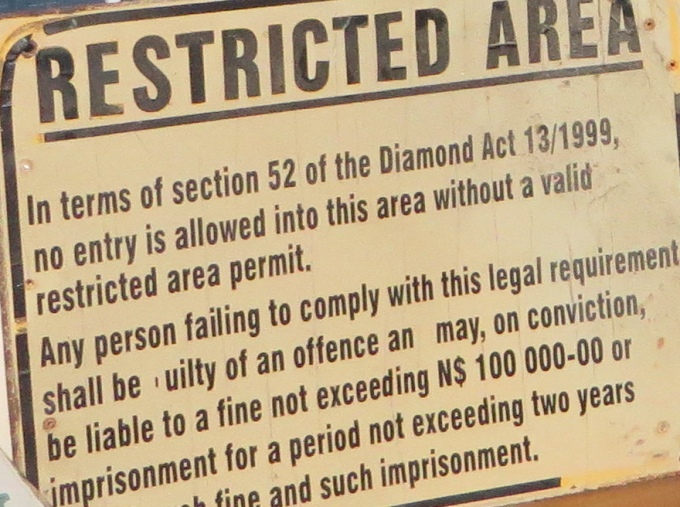

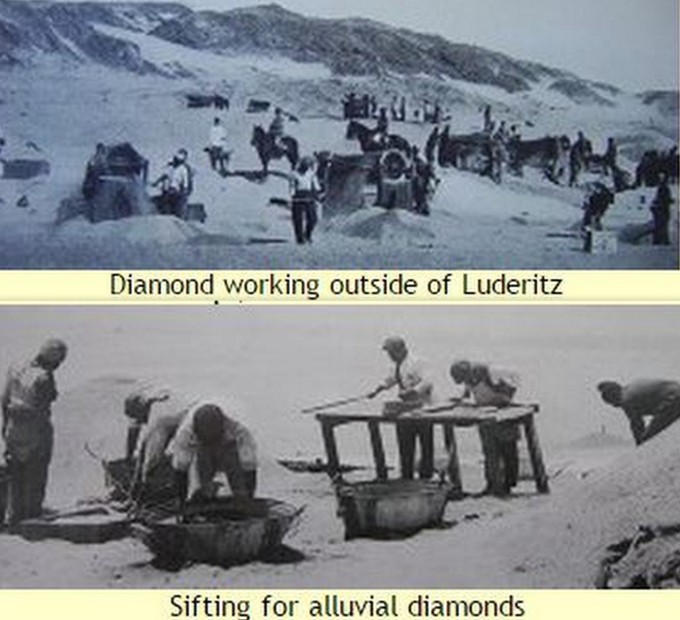

The German government originally created the Sperrgebiet in 1908 in its German South West Africa colony, after diamonds were first discovered. During WWI, Germany lost the territory to South Africa and the South African government gave control of the mining rights to DeBeers. After Namibia's independence, Namibia partnered 50/50 with DeBeers to form Namdeb Diamond Corporation. Sperggebiet remains. In fact, Namibia's Diamond Act of 1999, very explicitly outlines the rights of the diamond mining industry, the allowed legal actions of diamond inspectors and the laws governing uncut diamonds, as well as the penalties for possessing them illegally … stiff fines and lengthy imprisonment. I read that “some people in Namibia serve longer sentences for diamond theft than others do for murder”.

The town of Oranjemund located in the Sperggebiet is still inaccessible without a permit which “necessitates the submission of a police clearance document from your country of origin and can entail some months wait for Namibian authorities to approve the visit application.”

The diamond-mining industry has certainly left its mark on the area. Open-pit mining, spoil heaps and subsequent erosion and pollution, especially now along the coast, have done significant damage. On the other hand, only about 5% of the Sperggebiet is actually actively mined, the rest acts as kind of a buffer territory. The public exclusion from the area for decades has maintained much of the area as untouched. Granted it's semi-desert and desolate, but in actuality, it's a bio-diversity “hot-spot”. “About 1,050 plant species are found in the Sperrgebiet, which is 25 percent of the entire flora of Namibia. Fifty-six vegetation types have been identified, 35 coastal and marine bird species, 60 wetland bird species and 120 terrestrial bird species. There are 80 terrestrial and 38 marine mammal species, including 600,000 Cape fur seals, representing 50% of the world's seal population. Other wildlife includes 100 reptile species and 16 frog species.”

In 2004, Namdeb tranferred control of a large section of the Sperrgebiet to the Namibian government with the intent of reclaiming and re-vegetating the land and creating Sperggebiet National Park. In 2009, the park was formally opened, however unless you have a permit (which can take upwards of a week) and go with a nationally certified tour guide (there's only one in Luderitz), you are still not allowed to enter. We looked into the cost of taking the tour. They require a minimum of four people for the 8-hour tour and the cost is a whopping N$1,500/pp (~$US130/pp) for a marginal look at the area … a couple of ghost towns and a trip along the coast to a scenic arch formation. We can't imagine that many Namibians or tourists (like us) will have the opportunity to enjoy the park in the near future. Of course, what's the cost now for a day-pass to Disney World not counting transportation or lunch?